Mechanism of Action

PPIs exert their therapeutic effect by inhibiting the H+/K+ ATPase enzyme, commonly known as the proton pump, located on the parietal cells of the stomach lining. This enzyme plays a crucial role in the secretion of gastric acid. When stimulated by food intake, the proton pump exchanges potassium ions for hydrogen ions, resulting in the release of hydrochloric acid into the stomach.

PPIs are prodrugs, meaning they are administered in an inactive form and are activated in the acidic environment of the stomach. Once activated, they form a covalent bond with the cysteine residues on the proton pump, leading to irreversible inhibition. This mechanism effectively reduces gastric acid secretion, providing symptomatic relief and allowing for the healing of acid-induced damage to the gastrointestinal tract.

PPIs are most effective when taken approximately 30 minutes before a meal, as food stimulates the production of gastric acid, enhancing the drug's activation and efficacy.

Clinical Applications of Proton Pump Inhibitors

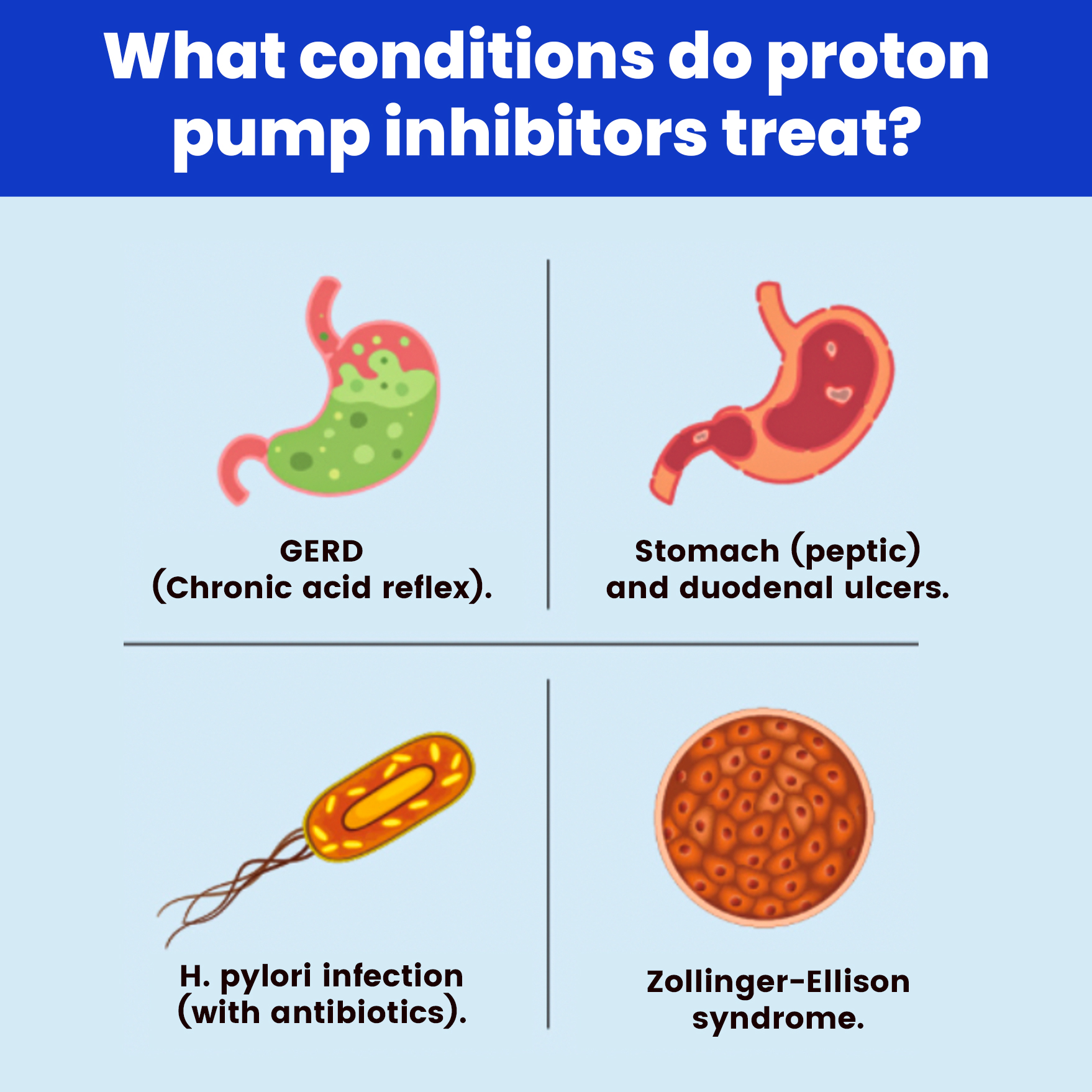

PPIs are indicated for a variety of conditions characterised by excessive acid production or damage caused by stomach acid. Some of the key indications include:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): GERD occurs when stomach acid refluxes into the oesophagus, causing heartburn, chest pain, and potential esophageal damage. PPIs are the first-line treatment for managing chronic GERD and healing erosive esophagitis.

- Peptic Ulcers: Peptic ulcers develop when the protective mucosal lining of the stomach or duodenum is eroded by stomach acid, often due to Helicobacter pylori infection or long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). PPIs aid in reducing gastric acid secretion, promoting ulcer healing and preventing recurrence.

- Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: This rare condition is characterised by gastrin-secreting tumours (gastrinomas) that cause excessive acid production, leading to severe peptic ulcers. PPIs are essential in controlling acid hypersecretion in these patients.

- Erosive Esophagitis: Caused by chronic acid exposure to the oesophagus, this condition can lead to inflammation, ulcers, and scarring. PPIs promote healing by reducing the acid load in the oesophagus.

- Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis: In critically ill patients, stress-induced ulcers can develop due to physiological stress from surgery, trauma, or severe illness. PPIs are often used prophylactically in high-risk patients to prevent the formation of these ulcers.

Pharmacokinetics and Dosing

PPIs are lipophilic weak bases that are absorbed in the small intestine and undergo hepatic metabolism primarily via the cytochrome P450 system, specifically through CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 enzymes. Given their irreversible inhibition of the proton pump, a single dose can suppress acid production for 24 to 48 hours. However, complete restoration of acid secretion requires the synthesis of new proton pumps, which can take several days.

The standard dosing for PPIs typically ranges from once daily to twice daily, depending on the severity of the condition being treated. For conditions such as GERD, a 4 to 8-week course is often prescribed, while conditions like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome may require indefinite treatment.

Long-Term Use: Risks and Emerging Concerns

While PPIs are highly effective, long-term use has been associated with several potential risks, many of which are still under investigation. Some of the most notable concerns include:

1. Nutrient Malabsorption

Chronic use of PPIs can lead to malabsorption of vital nutrients, particularly magnesium, calcium, and vitamin B12. Gastric acid plays a key role in facilitating the absorption of these nutrients. Hypomagnesemia, in particular, has been documented in long-term PPI users and can lead to muscle cramps, arrhythmias, and seizures. Similarly, reduced gastric acidity impairs the absorption of calcium, potentially leading to osteoporosis and an increased risk of fractures, particularly in the hip, spine, and wrist.

2. Increased Risk of Infections

Stomach acid acts as a first line of defence against ingested pathogens. Reduced acid secretion increases the risk of infections such as Clostridium difficile (C. diff) and pneumonia. Several studies have shown a correlation between long-term PPI use and an elevated risk of gastrointestinal infections, particularly in hospitalised patients. C. diff infections can cause severe diarrhoea and inflammation of the colon, posing a significant risk in vulnerable populations.

3. Kidney Disease

Emerging research has suggested a potential link between prolonged PPI use and the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, some studies have hypothesised that PPIs may trigger interstitial nephritis, an inflammatory condition of the kidneys that can progress to CKD over time.

4. Dementia and Cognitive Decline

Some observational studies have suggested an association between long-term PPI use and an increased risk of dementia. However, these findings remain controversial, and more research is needed to establish a direct causal relationship. Potential mechanisms include the disruption of the blood-brain barrier or nutrient deficiencies (e.g., vitamin B12) that may contribute to cognitive decline.

5. Gastric Cancer Risk

Chronic suppression of gastric acid may lead to hypergastrinemia, a condition characterised by elevated levels of the hormone gastrin, which stimulates acid production. Long-term hypergastrinemia has been linked to the development of gastric polyps and, in rare cases, gastric cancer. However, the overall risk remains low and is still under investigation.

Managing Long-Term PPI Use: Recommendations

Given the potential risks of long-term PPI use, healthcare providers are advised to regularly reassess the need for continued therapy. Some strategies for minimising risks include:

- Tapering off PPIs: Gradually reducing the dose of PPIs can help mitigate rebound acid hypersecretion, a condition where acid production temporarily increases after discontinuation of the drug.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Patients can benefit from lifestyle changes such as weight loss, dietary modifications, and avoiding triggers like alcohol, smoking, and large meals close to bedtime. These changes can reduce acid reflux symptoms and minimise the need for long-term PPI use.

- H2 Receptor Antagonists: In some cases, H2 receptor blockers like ranitidine or famotidine can be used as a less potent alternative to PPIs, particularly for mild or intermittent symptoms.

Conclusion

Proton pump inhibitors are highly effective in treating a range of acid-related gastrointestinal disorders, offering significant relief and healing for millions of patients worldwide. However, as with any medication, the benefits must be weighed against potential risks, particularly when used long-term. Patients on chronic PPI therapy should be regularly monitored, and alternative treatment strategies should be considered when appropriate.

For more such helpful blogs click here.

Claim your FREE career assessment session and receive tailored guidance for your global healthcare career!