Types of Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax can be caused by various factors, and each type is classified based on its cause.

Primary Pneumothorax

Also known as spontaneous pneumothorax or primary spontaneous pneumothorax, this type occurs without any apparent cause or underlying lung disease. Factors such as cigarette smoking, family history, or rupture of bullae (small air-filled sacs in the lung tissue) may contribute, but they do not directly cause pneumothorax.

Secondary Pneumothorax

Also referred to as non-spontaneous or complicated pneumothorax, this type results from underlying lung conditions such as COPD, asthma, tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, or whooping cough.

Tension vs. Non-Tension Pneumothorax:

A pneumothorax can also be classified as either tension or non-tension.

Tension Pneumothorax: This occurs when excessive pressure builds up around the lung due to a rupture in the lung surface, allowing air to enter the pleural cavity during inspiration but preventing it from escaping during expiration. The rupture acts as a one-way valve, leading to lung collapse.

Non-Tension Pneumothorax: This type is less severe as there is no ongoing accumulation of air, and therefore, no increased pressure on the organs and chest.

Traumatic Pneumothorax

This type is caused by physical trauma to the lungs, such as a stab wound, gunshot, or injury from a motor vehicle accident.

Iatrogenic Pneumothorax

This form develops as a result of medical procedures or incorrect medical care, such as an accidental puncture to the lung during surgery.

Causes and Risk Factors

The cause of primary spontaneous pneumothorax is iatrogenic (unknown). It may be due to:

- Gender

- Smoking

- Family history of pneumothorax

The secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in the context of various lung diseases. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is the most prevalent, accounting for approximately 70% of cases. Other lung conditions that significantly increase the risk of pneumothorax include:

- Asthma

- HIV with pneumocystis pneumonia

- Necrotizing pneumonia

- Tuberculosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bronchogenic carcinoma

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Severe ARDS

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- Collagen vascular disease

- Inhalational drug use like cocaine or marijuana

- Thoracic endometriosis

Other taumatic injuries:

Injury or trauma to the chest area: Bullet or stab wounds, fractured ribs, or blunt force trauma can cause the lungs to collapse.

Certain medical procedures: Procedures that may inadvertently puncture the lung, such as needle aspiration to drain fluid, biopsy, or the insertion of a large intravenous catheter into a neck vein, can lead to pneumothorax.

Activities with sharp changes in air pressure: Flying in an airplane or deep-sea diving can also result in a collapsed lung.

Epidemology

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax is most common in individuals aged 18 to 40, while secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is more frequent in those over 60 years old. In newborns, pneumothorax is a potentially serious condition, occurring in about 1-2% of all births.

The overall consultation rate for pneumothorax (both primary and secondary) in the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) was 24.0 per 100,000 annually for men and 9.8 per 100,000 annually for women. Hospital admissions for pneumothorax as the primary diagnosis had an overall incidence of 16.7 per 100,000 per year for men and 5.8 per 100,000 per year for women. Mortality rates were 1.26 per million per year for men and 0.62 per million per year for women.

Pathology

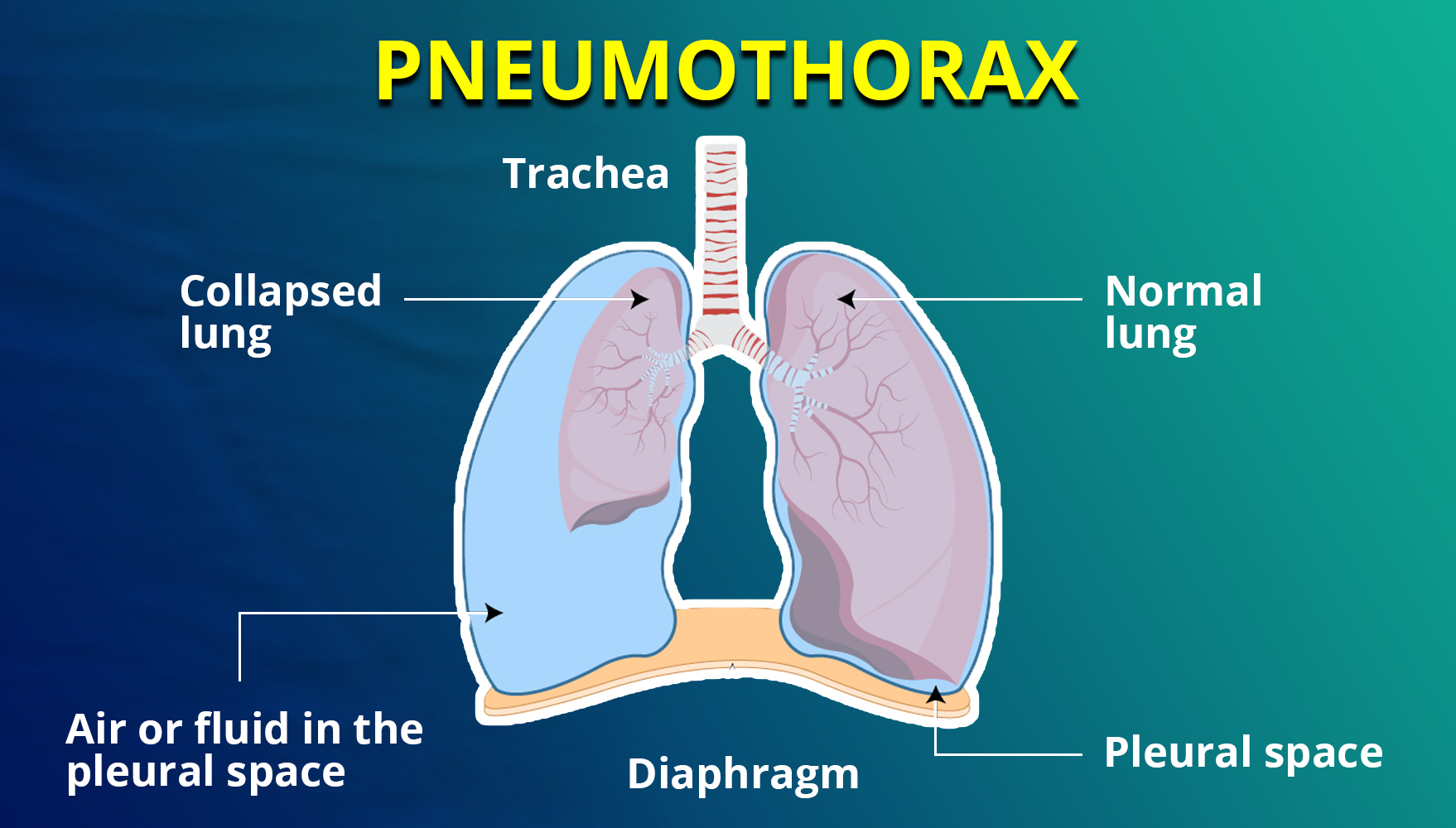

The pressure gradient in the thorax changes with pneumothorax. Normally, the pleural space pressure is negative compared to atmospheric pressure, allowing the lungs to expand with the chest wall. When air enters the pleural space from the alveoli or outside, it alters the gradient and causes lung collapse until equilibrium is achieved or the rupture is sealed. This leads to a decrease in vital capacity and oxygen levels.

Spontaneous pneumothorax usually results from the rupture of bullae or blebs. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs without underlying lung disease, often in tall, thin young people and smokers due to inflammation and oxidative stress. Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is associated with lung diseases like COPD, tuberculosis, and cystic fibrosis.

Iatrogenic pneumothorax is caused by medical procedures, with thoracentesis being the most common cause. Traumatic pneumothorax results from chest trauma, creating a one-way valve effect, and is common in ICU patients on positive-pressure ventilation, leading to hemodynamic compromise.

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of pneumothorax are:

- Sudden onset of chest pain, often sharp and worsening with inspiration

- Shortness of breath (dyspnoea)

- Increased heart rate (tachycardia)

- Increased respiration rate (tachypnoea)

- Dry cough

- Fatigue

- Signs of respiratory distress, such as nasal flaring, anxiety, and the use of accessory muscles

- Low blood pressure (hypotension)

- Subcutaneous emphysema

Diagnosis

The initial step in diagnosing pneumothorax involves a thorough medical and physical examination.

Auscultation

During chest examination with a stethoscope, decreased or absent breath sounds over the affected lung area indicate that the lung may not be inflated in that region. Additionally, hyperresonance (higher-pitched sounds than normal) upon chest wall percussion suggests pneumothorax.

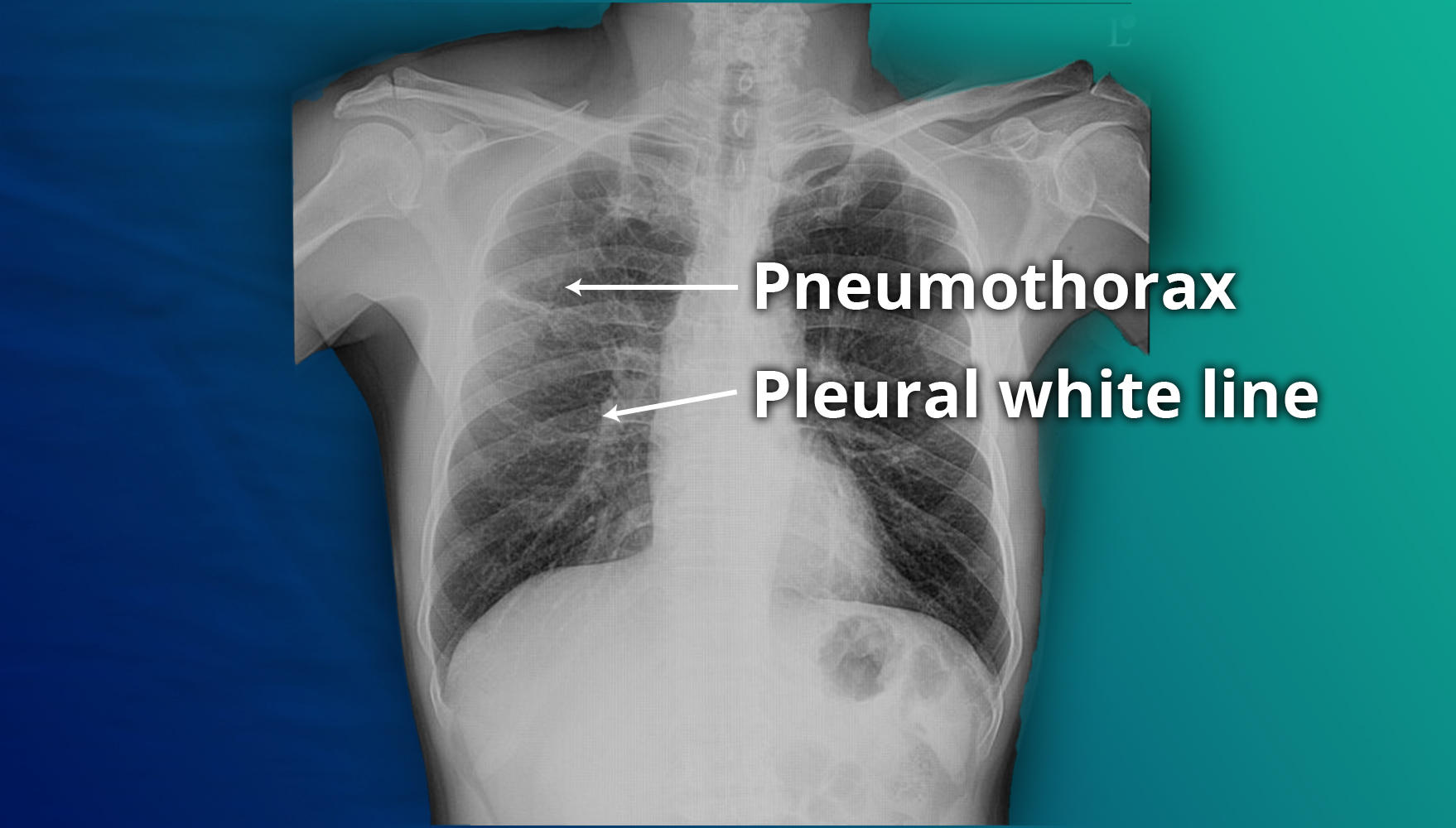

Imaging

Chest X-rays are used to confirm the diagnosis. In a supine chest X-ray, a deep sulcus sign—characterized by a low lateral costophrenic angle on the affected side—is diagnostic. The presence of air outside the normal lung airways and shifting of organs away from the air leak in the thoracic cavity also indicate pneumothorax.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound scans can also assist in diagnosing pneumothorax.

Treatment

Management of pneumothorax depends on the clinical scenario:

Needle Decompression: For symptomatic and unstable patients, performed with a 14- to 16-gauge angiocatheter in the second intercostal space at the midclavicular line.

Thoracostomy Tube: Inserted for stable pneumothoraces or after needle decompression. Placed in the fifth intercostal space at the midaxillary line, with size adjusted based on patient factors.

Open Chest Wounds: Initially treated with a three-sided occlusive dressing, followed by possible tube thoracostomy and chest wall repair.

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax:

- Asymptomatic and <2 cm: Discharge with follow-up in 2-4 weeks.

- Symptomatic or >2 cm: Needle aspiration; if residual depth <2 cm, discharge; otherwise, tube thoracostomy.

Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax:

- <1 cm and no dyspnea: Admit, give high-flow oxygen, observe for 24 hours.

- 1-2 cm: Needle aspiration, observe post-aspiration size; <1 cm, manage with oxygen and observation; >2 cm, tube thoracostomy.

- 2 cm or dyspnea: Immediate tube thoracostomy.

Supplemental Oxygen: Increases reabsorption of air from the pleural space by changing the pressure gradient.

Surgical Intervention: Indicated for continuous air leaks >7 days, bilateral pneumothoraces, high-risk professions, recurrent ipsilateral or contralateral pneumothorax, and patients with AIDS. Options include VATS with pleurodesis or thoracotomy. Mechanical pleurodesis (e.g., stripping pleura or using abrasive pads) and chemical pleurodesis (e.g., talc, tetracycline) reduce recurrence rates.

Physiotherapy Management

Indications for physiotherapy for pneumothorax are:

- Lung collapse

- Sputum retention

- Ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch

- Increased work of breathing

- Blood gas abnormalities

- Post-operative intensive care unit (ITU) care

Goals for Physiotherapy

The goal of physiotherapy management are as follows:

1.To improve ventilation and increase PaO2 levels

- Engage in physical activities such as stair climbing, walking, and moderate-intensity aerobic exercise.

- Perform active cycle of breathing exercises.

- Use sputum removal techniques like percussion and cough assist.

- Employ Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) devices.

- Practice incentive spirometry.

- Utilise non-invasive ventilation (NIV).

2. To assist in sputum removal

- Apply postural drainage techniques.

- Perform active cycle of breathing exercises.

- Use percussion, shaking, and vibrations.

- Utilise PEP devices.

- Engage in physical activities like stair climbing, walking, and moderate-intensity aerobic exercise.

- Practice coughing and huffing (forced expiratory breath).

- Conduct airway suctioning.

3. To reduce work of breathing

- Optimise body positioning.

- Practice breathing control techniques.

- Use relaxation techniques.

- Employ accessory muscle use strategies.

4. To improve exercise tolerance

- Implement early mobilisation and positioning.

- Follow a graded exercise program.

- Perform breathing exercises.

Physiotherapy Outcome Evaluation:

- Measure respiratory rate.

- Monitor O2 saturation.

- Assess arterial blood gases.

- Determine additional O2 requirements.

- Perform auscultation.

- Review chest X-ray.

- Evaluate mobility status.

For questions and preparation strategies for the exam, join the exclusive APC Written Assessment Preparation Course by Academically.

Fill out this form to get one-on-one counselling with our expert.